Earlier this year, BioSpace tallied up the hottest U.S. biotech start-ups in their NextGen Bio Class of 2020 – Anthos Therapeutics was ranked #2.

Earlier this year, BioSpace tallied up the hottest U.S. biotech start-ups in their NextGen Bio Class of 2020 – Anthos Therapeutics was ranked #2. Anthos focuses on developing drugs for cardiovascular disease, especially for high-risk patients. Their goal? To develop next-generation anticoagulants that don’t have the bleeding risks current blood thinners have. Their lead drug is also long acting, meaning patients may only need to take it monthly versus daily.

If their drug pans out in clinical trials, it could be great news for the millions of people affected by cardiovascular diseases each year. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., killing 647,000 Americans each year (about 1 in 4 of all U.S. deaths). Thrombosis, when a blood clot blocks the blood vessel, can cause heart attacks or strokes, which together cause a quarter of all deaths worldwide.

“Forty-five percent of people at risk of thrombosis are untreated or sub optimally treated, largely due to the fear of bleeding,” John Glasspool, CEO and President of Anthos, told BioSpace. “The unmet needs in cardiovascular disease really deserve more attention. We’re pleased to develop drugs in an area other companies aren’t focusing on as much.”

BioSpace spoke with Glasspool about how Anthos was formed, what the company has been up to and its lead drug candidate Abelacimab (also called MAA868).

A unique company model

This Cambridge, MA-based company was built for optimization, combining parts of a small biotech with the power of a large pharma company. Glasspool described their company structure as a “hybrid externalized model” – it combines senior leadership at the company to oversee drug development, manufacturing, and regulatory quality with the actual development and manufacturing done through external partners.

A recent example is Anthos’s collaboration with manufacturing giant Lonza to further develop Abelacimab. “Our partnership with Lonza provides Anthos Therapeutics access to its world-class development and manufacturing expertise,” Anthos Co-Founder and COO Jonathan Freeman, Ph.D. said in the company’s press release.

This novel business model was pioneered by Anthos and Lonza to link products, cash flow, and value generation, aligning the needs of the company with their investors. Basically, it provides the quality and output of a larger pharma company with the decision-making speed of a small biotech.

“Our mission is to develop drugs with the same quality as a large biopharmaceutical company with much more capital efficiency,” Glasspool said.

The company was founded by Blackstone Life Sciences and Novartis. Blackstone Life Sciences, who controls the development of the company’s products, launched the company in February 2019 with $250 million in initial funding. Although Abelacimab was originally developed at Novartis, Novartis passed the baton to Anthos, licensing Abelacimab to them so they could build on Novartis’s early-phase development.

Getting to the heart of the matter

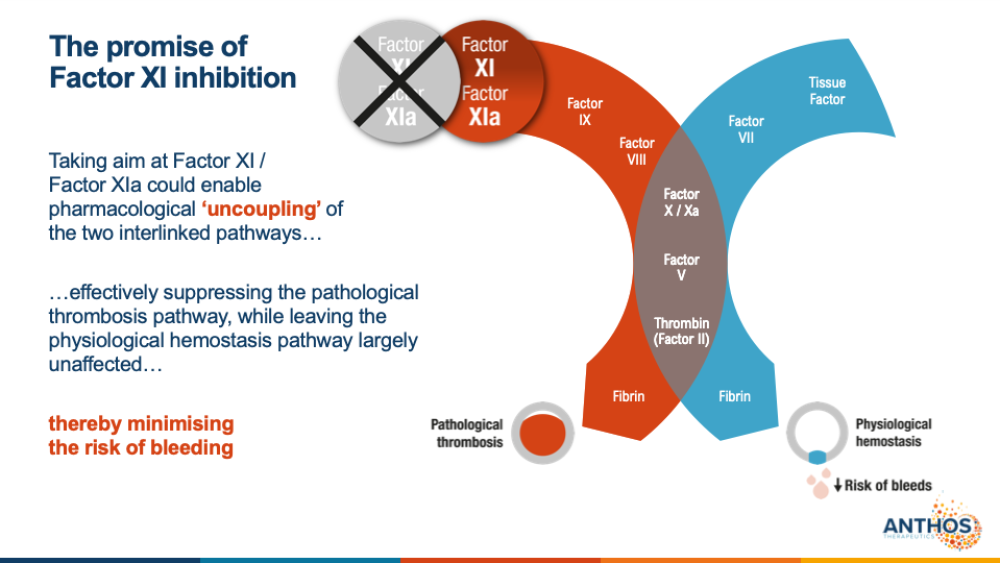

Abelacimab is an antibody that targets a specific blood clotting protein (factor XI), which is important for one arm of the blood clotting pathway. Soaking up factor XI prevents it from activating other clotting factors, severing the chain reaction of coagulation from the beginning.

Abelacimab is one of the next-generation anticoagulants being pursued against the promising factor XI target. Unlike other factor XI-targeting blood thinners in development, Abelacimab has dual activity – it binds to both the inactive and active forms of the clotting factor. Previously characterized at Novartis, Abelacimab has a unique binding mode, trapping both protein forms in an inactive conformation.

“The dual activity of Abelacimab causes profound suppression of factor XI, which we believe will bring about the greatest clinical benefit,” Glasspool commented.

The key to Abelacimab? The possibility of reducing blood clot risk without increasing bleeding risk. Because factor XI and its active form (called factor XIa) are more involved with thrombosis than normal blood clotting (called hemostasis), this drug is expected to selectively prevent thrombotic, vessel-blocking blood clots without disrupting blood clotting after an injury.

“We believe that Abelacimab is the first hemostasis-sparing anticoagulant,” Glasspool said. “Current conventional anticoagulants operate within normal hemostasis and pathological thrombosis by targeting factor II or X. Abelacimab has the promise to uncouple the prevention of thrombosis from the risk of bleeding.”

Conventional blood thinners, such as rivaroxaban (Xarelto) and apixaban (Eliquis), block clotting factor Xa, whereas Warfarin interferes with Vitamin K activity, which is needed to produce factors II, VII, IX, and X. Heparins also block factor Xa production indirectly by activating another factor Xa-inhibiting protein.

Factor Xa is at the crossroads of both arms of the coagulation pathways, meaning it impacts both thrombosis and normal blood clotting. On the other hand, factor XI only impacts one arm, allowing for clotting selectivity.

“Focusing on factor XI inhibition is where we believe we can leave normal hemostasis intact while protecting from thrombosis in vessels,” Glasspool explained. “This paradigm shift to factor XI is important to provide protection with a much lower risk of bleeding, enabling more people to get treated.”

Learning from nature

What happens when you block factor XI? Thanks to genetics, we already know the answer. Factor XI deficiency is a disorder where there is a mutation in the factor XI gene, creating a lack of clotting factor. Depending on how much functional factor XI is present the person classifies their disease as partial or severe.

The majority of those affected have relatively mild bleeding problems; in fact, some mild cases even have few if any symptoms. Importantly, severe issues seen with other bleeding disorders, like bleeding into the gastrointestinal tract, skull, or joints, are very rarely seen in this disorder.

Notably, people with factor XI deficiency also seem to be protected from thrombotic diseases, such as stroke and deep-vein thrombosis (DVT). The flip side told the same story – people with elevated factor XI levels in their blood have a higher risk of stroke and blood clots in the veins (venous thromboembolism). This initially garnered interest in focusing on factor XI and XIa as a novel antithrombotic agent.

Why develop an antibody drug?

Most currently available blood thinners are small molecules available as pills. So, why did Anthos go for an antibody anticoagulant?

“We’ve taken a very patient-centric and real-world evidence approach,” said Glasspool. “An antibody can convey some significant benefits in terms of patient management and optimization.”

One benefit is the way an antibody is cleared from the body, avoiding issues with renal insufficiency that traditional small molecule blood thinners may face. Because many patients at risk of thrombosis are older, they tend to have other co-morbidities, such as renal impairment or liver disease, which can affect how drugs are processed. Small changes in a patient’s renal function may also have a large effect on anticoagulant levels in the blood, putting patients at a higher risk of bleeding.

“Each time a patient needs to get a dose adjustment due to side effects, it is seen as a failure by the patient,” Glasspool commented. “Not having to worry about possible renal or liver function provides a significant benefit to patients.”

Another benefit is lower likelihood of an antibody interacting with other medications, compared with small molecule drugs. Patients may be taking multiple medications for other conditions.

The once monthly dosing of Abelacimab is an added convenience to patients and their caretakers. Reducing the dosage burden from one or even twice daily to monthly also increases adherence. “Adherence is important for any medication, but especially for anticoagulants, where missing a dose might lead to a period of time when a patient is not protected from thrombotic complications,” Glasspool added.

Unlike other antibody drugs that are given via intravenous (IV) infusion, Abelacimab is given as a subcutaneous injection. Despite the benefit of at-home administration, some patients may not like the idea of giving themselves an injection under the skin, possibly limiting the drug’s utility for some patients.

The long-term length of blood thinning activity also poses an interesting challenge – what if a patient needs to have surgery? Again, we can turn to nature. Patients with factor XI deficiency have successfully undergone invasive procedures and surgical operations without major bleeding complications.

As a cautionary measure, Anthos will be developing a strategy to reverse Abelacimab’s thinning effects to prevent bleeding complications from surgeries. “While we believe the risk of bleeding is low, making sure a reversal strategy is in place is a key part of our clinical development program,” added Glasspool.

Preclinical and clinical results

In previous preclinical studies by Novartis, non-human primates treated with Abelacimab had “sustained anticoagulant activity […] without any evidence of bleeding.” In their first-in-human study, the company reported that Abelacimab was well tolerated and its activity lasted for at least 4 weeks.

A few years ago, Novartis listed two Phase II trials studying Abelacimab on ClinicalTrials.gov, but withdrew the studies before enrolling patients. Now, the drug is being carried forward by Anthos in a randomized, placebo-controlled Phase II trial in an estimated 48 adults with atrial fibrillation (Afib), or irregular heart rate.

A major complication of Afib is developing blood clots in the heart that can find their way into the circulation and lead to a stroke; this is why blood thinners are usually prescribed along with medications to regulate heart rate. Afib patients need to be protected long-term, so finding novel anticoagulants with minimal bleeding risk is key.

“Our Phase II studies will demonstrate the proof-of-concept of efficacy and relevance in terms of bleeding reduction,” Glasspool concluded. “We will be able to establish the value of Abelacimab versus the current competitors and guide our future clinical plans.”

Although their Phase II program was paused due to COVID-19 earlier this year, it has since resumed. Glasspool said they “should be able to keep all their planned timelines despite the COVID-19 intervention. This is critical because so many patients need this therapeutic for their protection.”