Exo Therapeutics’ approach is not only different, it has revolutionary potential.

Exosite Advantage/Courtesy of Exo Therapeutics

The acknowledgment that we, as scientists and as people, have barely scratched the surface of the possible body of knowledge is a powerful driver of discovery. Actually making those discoveries, however, requires a flexible way of thinking that enables people to embrace new insights, and to pivot as needed.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned in my career is to be open-minded and constantly learning,” Michael Bruce, CEO of Exo Therapeutics, told BioSpace. Thinking you know almost everything about a subject is narrowing. This open-minded mentality is pervasive at Exo as it discovers previously unconsidered sections of enzymes as new druggable targets.

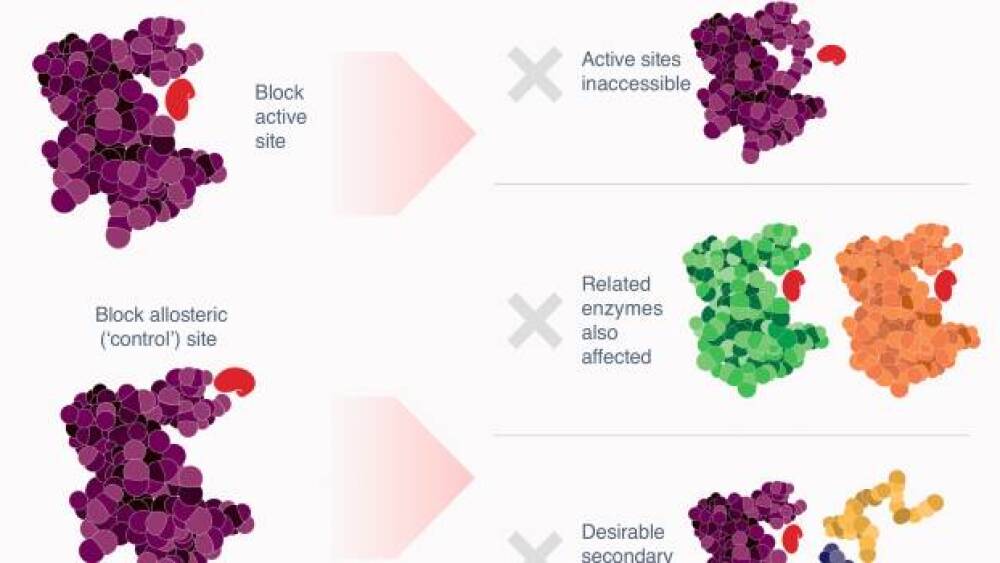

Oftentimes, drugging targets is described as a key and lock exercise or a jigsaw puzzle in which a therapeutic compound fits (ideally) a single pocket. Exo Therapeutics’ approach is not only different, it has revolutionary potential. Exo is discovering druggable targets that bind to exosites. These distal, substrate-enzyme junctions are unique to specific enzyme-substrate interactions. They have the potential to reprogram enzyme activity to achieve precise, robust therapeutic effects and, in the process, solve multiple targeting and specificity challenges that plague traditional binding targets, including active and allosteric sites.

“Exo is part of the renaissance triggered by the past decade’s advancements in technology, and is an extension of discoveries made by co-founders David Liu, Ph.D., of the Broad Institute; Alan Saghatelian, Ph.D., of the Salk Institute; and J.P. Maianti, Ph.D., of Harvard University,” Bruce said. “A lot of proteins and enzymes connect in amazing ways…” that are beyond what drug developers consider the active sites.

The founding scientific research was based on insulin-degrading enzyme. “If you shut insulin-degrading enzyme down by traditional active site methods, you will struggle to achieve glycemic control since active-site drugging shuts down elimination of both insulin and glucagon. You don’t want that,” Bruce explained.

“Liu discovered a pocket away from the active docking site. It’s druggable and is the right size, shape and depth. Later, they found some small molecule inhibitors that cause insulin to be blocked, preserving it, while allowing glucagon, which is smaller, to slip by and be degraded.” Exo was subsequently founded with the promise of extending this scientific concept to other targets.

That ability to find and model distal druggable spaces enables the team to reprogram enzymes with small molecules. This proprietary capability is what Bruce said is unique about the company. Already, several hundred exosite targets are in its database, which can be scored using proprietary analytics.

When Bruce joined Exo Therapeutics in early 2020, “I wanted to have a direct line of sight to the impact on patients,” he said, adding that a close family member who has lung cancer with an ALK1 mutation greatly benefited from innovative therapeutics. “I wanted to have that kind of impact.”

Today, he said, “Two-thirds of all approved medicines are still small molecules.” Consequently, “I wanted to work with a small molecule company. We know the regulatory steps, how to make it and how to deliver it, and I wanted a company that was developing a platform drug.” He wanted, most of all, to develop a solution to an intractable problem. “Right at the beginning, I knew that Exo Therapeutics had a lot of potential. After meeting the founders, I was impressed.”

Apparently, so were they. Bruce had more than 20 years’ experience in the biotech industry, was a member of the roadshow team for Kaleido Biosciences’ IPO and was an early CRISPR Therapeutics employee, managing product development and alliances that included deals with Vertex and Bayer. “I’ve done a wide variety of things, from bench science to business,” he said.

Therefore, he was well-versed in one of the leading challenges of the day…what he called “the Phase III problem.” It was present during his early career, and it’s present today. As he explained, “We didn’t always know where the drug was going and whether it was hitting targets we didn’t expect, so we couldn’t always achieve a therapeutic index. Our screening technology didn’t always show it, and you often didn’t find out until you were far into clinical trials.” Exo Therapeutics solves at least part of that problem.

This early-stage company hasn’t disclosed its target list but is initially developing four solutions for oncology or inflammation: one for precision indications, one that is targeting a well-validated synthetic lethality, one for solid tumors and one for an enzyme that performs multiple functions.

“Our first program addresses targets for which the biology is well-established but are undruggable – for example, the active site isn’t readily accessible.” In synthetic lethality, one protein is mutated or missing, which allows another target also to be susceptible.

A second program targets a protein that has been challenging because of off-target effects on members of the target class that have very similar active sites. Existing drugs tend to hit them all because of their similarity, oftentimes causing adverse side effects. Targeting exosites enables more precision.

A final program involves targeting one activity of a pleiotropic enzyme using an approach similar to the founding research on insulin-degrading enzyme. “The challenge is that most efforts to drug this enzyme shut down all their activities rather than just the one that’s clinically relevant.

“We don’t expect to be in the clinic until at least the end of 2023,” Bruce said.

Advancing new science is always risky, he acknowledged. Bruce mitigates much of that risk by accepting the science – “even when we don’t like it” – and hiring the best and brightest. The trick is not just to hire the best people you can, but to hire those who can work well together, he said.

“I’ve worked on teams of less experience that worked together incredibly well and did great things. I’ve also seen a team of high-powered people bog down because egos got in the way.”

He saw that in school, too, where he worked as a guitarist to help pay his non-tuition expenses. “I’ve been in a number of bands. Two were composed of superstar players, but they didn’t play well together, and others may have had less experienced individuals, but they worked together and made the music sound great.”

Bringing out the best in a team is a primary role for CEOs, he said. “My job is to work with the smartest people and to become the second-best expert on everything. They will be the main expert. That’s the best way to help the team get what it needs.”

To coach Exo Therapeutics as a team while still developing individuals, “I actively spend time talking with my staff of 20 plus about how to work together, how to make decisions, how to disagree and what it feels like when 60% support a decision but 40% don’t. These are the cultural things that can make or break a company.”

The other point is to realize that management styles must change as the company grows. Bruce is thinking about that now, preparing for the next growth phase that eventually will transform Exo into a multiproduct company.