The rate of incidence of infection by Naegleria fowleri in the U.S. is very, very low. But there’s something about picking up an incurable, brain-eating amoeba by swimming in freshwater lakes and rivers that understandably freaks people out.

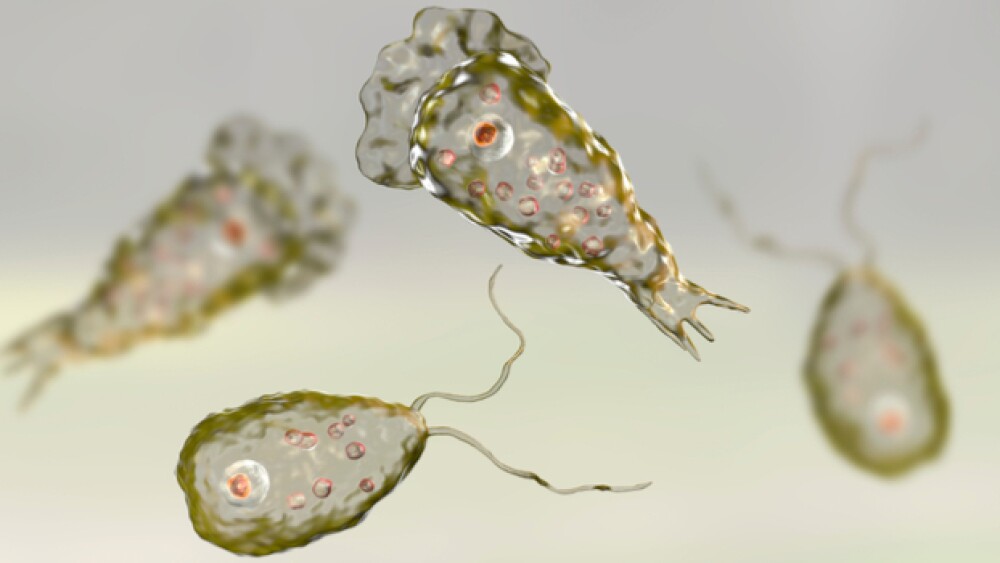

Flagellate forms and trophozoites of the parasite Naegleria fowleri.

The rate of incidence of infection by Naegleria fowleri in the U.S. is very, very low. But there’s something about picking up an incurable, brain-eating amoeba by swimming in freshwater lakes and rivers that understandably freaks people out.

N. fowleri causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis (PAM), which is a brain infection that causes destruction of brain tissue. Symptoms start about five days after infection, and include headache, fever, nausea, or vomiting. Later symptoms include stiff neck, confusion, lack of attention, loss of balance, seizures, and hallucinations. Once symptoms start, the disease moves fast and usually causes death within about five days.

In the U.S., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), from 2008 to 2017, there were only 34 reported infections. Of those, 30 were infected by recreational water, three were infected from performing nasal irrigation using contaminated tap water, and one was infected by contaminated tap water used in a backyard slip-n-slide.

Now, researchers believe they have identified a way to kill the amoeba. Researchers with Sunway University in Malaysia and the University of Karachi in Pakistan published their research in the journal ACS Chemical Neuroscience.

The treatment involves binding silver to already approved seizure drugs. Their research shows that combination can kill the amoebae while leaving human cells alone.

Ayaz Anwar, a researcher at Sunway University, who led the research, told The New York Times, “The biggest challenge is finding a drug that can actually reach the right region of the brain. We need a drug that can trick the body into letting it through—and we know that anti-seizure drugs can overcome that barrier.”

They started with three anti-seizure drugs, diazepam, phenobarbitone and phenytoin, that the amoebae are sensitive to. They then bound the drugs to silver particles about 50 to 100 nanometers in diameters, or about one-thousandth the width of a strand of hair, The Times says.

Although all three drugs worked in killing the amoebae over time, diazepam was twice as effective when combined with silver.

“Here is a nasty, often devastating infection that we don’t have great treatments for,” Edward T. Ryan, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s infectious diseases division, told The New York Times. “This work is clearly in the early stages, but it’s an interesting take.”

There have only been 143 people infected with the amoeba since 1962 in the U.S., and only four have survived. More than half occurred in Texas and Florida, related to the amoebae’s thriving in pond water. N. fowleri grows best at temperatures up to 115 degrees F (46º C). However, the CDC says it can be found in lakes or river sediment at much lower temperatures than found in the water.

In December 2018, Bossier City, located in northwestern Louisiana, conducted a 60-day chlorine flush of its municipal water system after N. fowleri was identified in the system on October 2. Once the flush is done, the state plans to test the water again. Bossier City Spokeswoman Traci Landry told the Shreveport Times, “With the state holiday schedule, we do not anticipate having results back until early to mid-January.”

The CDC indicated infections would not occur by drinking the water. It needs to end up in the nose, then infect the mucous membranes in the nasal cavity, migrate along the olfactory nerves and invade the brain.

In October 2018, a 29-year-old man, Fabrizio Stabile, died after being infected by N. fowleri. He reportedly picked the infection up at BSR Cable Park’s Surf Resort in Waco, Texas, where Stabile was vacationing. He lived in New Jersey.

Stabile complained of a headache on Sept. 16 and died on Sept. 21.

In an article about Stabile, Wired notes, “As rare as PAM is, the amoeba that causes it is common in freshwater. Epidemiologists have found it in lakes and rivers as far north as Minnesota, which saw its first case of PAM in 2010, and in pools, water parks, and municipal water systems across the American south. Researchers at the CDC have gone so far as to call it ubiquitous. Those same researchers predict its range will only expand, as global temperatures increase.”

From a diagnostics perspective, the CDC, the U.S. Geological Survey and Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute are working on tests that can monitor Naegleria in real-time. Part of that development is also smaller, mobile, modular devices that can be both used to identify the presence of the amoebae, but also potentially perform real-time genetic analysis.

In addition, researchers with the University of California San Diego are working on developing treatments for PAM. They published research in September 2018 in the journal PLOS Pathogens describing the work. They identified three new molecular targets to treat the drug, as well as several drugs that can slow it or kill. “It’s a starting point,” Anjan Debnath, co-author of the study and a parasitologist at UCSD, told Wired. “It shows we can find more potent compounds for fighting Naegleria fowleri.”