In a line of dominos, if you take out a single piece, the last one will never fall. Similarly, a lot of pieces have to line up and be pushed at the same time in a cell to result in cancer.

COLD SPRING HARBOR, N.Y., Dec. 1, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- In a line of dominos, if you take out a single piece, the last one will never fall. Similarly, a lot of pieces have to line up and be pushed at the same time in a cell to result in cancer. Twenty-two years ago, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Alea Mills discovered the protein p63. More recently, she found that a specific version of p63 (∆Np63α) causes cancer when it is overactive. Mills and her colleagues have been trying to devise ways to turn it off, but to no avail. Now they have found a way to stop the dominos from falling, not by turning off ∆Np63α itself, but by turning off other proteins that work together to activate it.

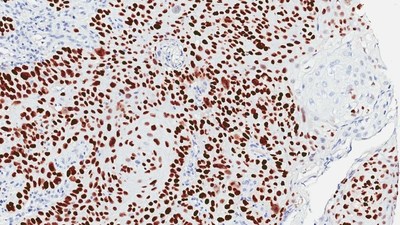

p63 regulates stem cells, which are immature cells that have the potential to grow into different kinds of mature cells. When one variant of the protein, ∆Np63α, is overactive, stem cell production never turns off. When that happens in squamous cells, which form the covering of the skin and many other organs, stem cells grow out of control and form tumors. These cancer stem cells invade other tissues and even wrap around the nerves of the face. The tumors can be painful, disfiguring, and difficult to remove. Mills says:

"I think of the cancer stem cells as kind of like a bad seed in your garden that will grow a weed if not surgically removed or somehow controlled."

Mills' team identified a cascade of four proteins that act like a series of dominos to activate ∆Np63α. Some of these proteins were already known to be involved in promoting other kinds of cancer, so there were already drugs in clinical trials to deactivate them.

When the Mills group added these drugs to patient-derived cancer stem cells growing in a Petri dish, the cells became less aggressive, less mobile, and slower growing. Mice with these cancerous squamous cells treated with these drugs developed smaller tumors.

Matt Fisher, a postdoctoral fellow in Mills' lab who led this study that was published in Cancer Research, says, "Squamous cell cancer is not an easy cancer to treat right now, and there's not a lot of therapeutic options. This is why we think identifying pathways that include druggable targets is so important." The discovery of four new therapeutic targets for this disease offers new hope for treating this deadly cancer.

About Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory

Founded in 1890, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory has shaped contemporary biomedical research and education with programs in cancer, neuroscience, plant biology and quantitative biology. Home to eight Nobel Prize winners, the private, not-for-profit Laboratory employs 1,100 people including 600 scientists, students and technicians. For more information, visit www.cshl.edu

![]() View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/breaking-the-chain-that-culminates-in-cancer-301435313.html

View original content to download multimedia:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/breaking-the-chain-that-culminates-in-cancer-301435313.html

SOURCE Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory