Congress did not reauthorize the rare pediatric disease priority review program at the end of 2024. Advocates say the ripple effect is already being felt across biopharma.

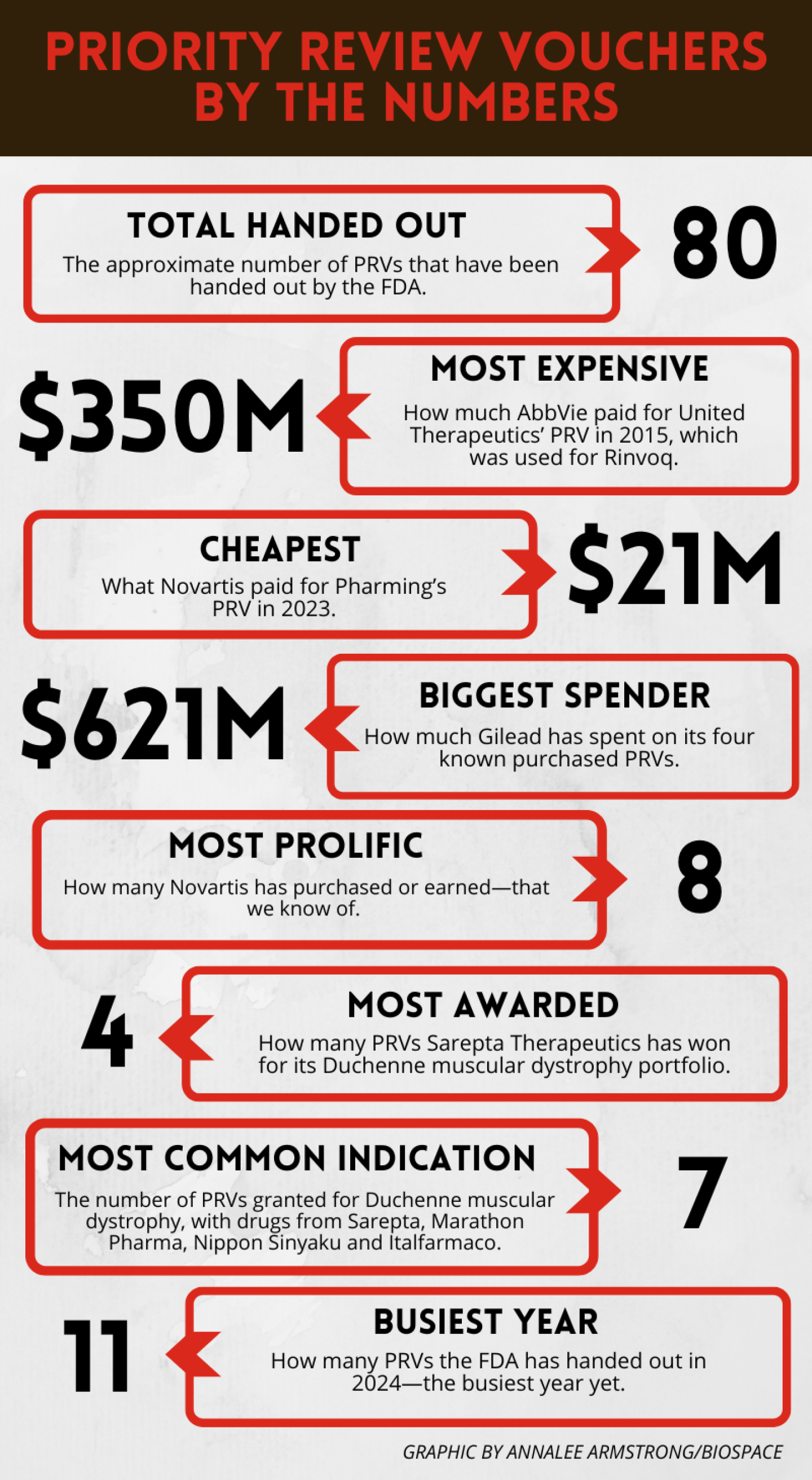

The FDA has never handed out more priority review vouchers than it did in 2024. Depending on who you ask, that’s a sign that the program is working or that pharma is reaping huge benefits in a quid pro quo situation of the government’s own making. But now rare disease biotechs have been left scrambling, as Congress did not renew the rare pediatric disease portion of the program at its end of year deadline despite bipartisan support.

“The impact on the rare disease drug developers and the investment community [is] already being felt because of the destabilizing effect of the failure to reauthorize the program prior to its expiration,” Stacey Frisk, executive director of the Rare Disease Company Coalition, told BioSpace in an interview. Her group is lobbying for a renewal to be tacked on to congressional efforts to address a looming March 14 budget deadline. “So really, the timeline is as soon as possible.”

The priority review voucher (PRV) rare disease program, which began in 2012, had unanimous renewal support from the 118th Congress, which ended on Jan. 3, according to Frisk. The program passed the House without issue and was listed among the priorities for the resolution to avoid a government shutdown. But the health programs that included the PRV program—which had already begun to sunset—were stripped from the continuing resolution at the last minute.

Despite the bipartisan support, the PRV program “got caught” as Congress’ timelines and priorities changed at the last minute, Matthew Winton, chief operating officer of Inozyme Pharma and a rare disease advocate, told BioSpace.

A bill called the Give Kids a Chance Act of 2024 has now been proposed to get the PRV program moving again, as Congress works to avoid the shutdown.

“Time is . . . sort of running out,” Winton said. “We need action on this immediately to continue the program but also continue investment in these pediatric rare diseases.”

The FDA notified drugmakers in the fall that, absent the renewal passing, the agency would have to stop handing out the coveted fast-pass vouchers, which expedite the drug review timeline from 12 months to about 6. The vouchers can be bought and sold, which provides a valuable fundraising boost for tiny rare disease biotechs. The current going rate on the open market is $150 million, the price Zevra Therapeutics earned just last week for its voucher that was granted from the September 2024 approval of Miplyffa. According to Winton, the cost of PRVs has risen to this rate as companies foresee the end of the program.

Without renewal, the FDA began sunsetting the program as of December 20, 2024. The agency cannot award any new vouchers unless the drug already had the rare pediatric disease designation. If Congress does not act, companies with existing designations will only have until September 30, 2026, to get their drugs approved in order to earn a voucher.

Already, companies with the rare pediatric disease designation for drugs in development are reeling, with many starting to warn investors in Securities and Exchange Commission filings that they may never get their coveted vouchers despite working for years to position for one. Winton said that companies make decisions to develop a drug years in advance, so having the rug pulled out suddenly due to a policy change can halt external investment.

“With that uncertainty, you’re going to get a slowdown in decision making. You’re going to get a slowdown in people investing in R&D programs,” Winton said.

See BioSpace’s full analysis here.

Quid Pro Quo

The industry has spent at least $513 million on buying vouchers that were earned in 2024, although more could have been sold without public disclosures. These non-dilutive proceeds are often used by smaller companies to bolster their overall clinical programs.

In a recent case that underscores the stakes, bluebird bio fought hard to get one for its sickle cell disease gene therapy Lyfgenia, which was approved in December 2023. Bluebird had already lined up a buyer before it even received the approval, according to SEC documents dated October 2023. Novartis agreed to pay $103 million for the voucher if it were granted.

While bluebird was granted rare pediatric disease designation in May 2020 for the treatment, the FDA did not hand out the coveted voucher. Bluebird appealed and was ultimately rejected three times. The agency did, however, hand one out to Vertex Pharma for rival gene therapy Casgevy, which was developed with CRISPR Therapeutics and approved on the same day as Lyfgenia.

This unsuccessful effort was cited in bluebird’s recent announcement that it would sell itself to private equity firms in a deal valuing the gene therapy maker at just $30 million. Bluebird did not have enough cash to operate past the first quarter but had spied positive revenue later in the year.

Eleven of the valuable trading cards were handed out to biopharma companies over 2024, across the three different programs that offer the vouchers. For the rare disease program specifically, indications that benefitted include sickle cell, Niemann-Pick type C, Duchenne muscular dystrophy and glioma, among others. With the pediatric rare disease program sunset announced, the FDA has handed out two already this year to Novo Nordisk for hemophilia A therapy Alhemo and Neurocrine Biosciences for congenital adrenal hyperplasia drug Crenessity.

There are two other ways to get one beyond the rare disease program: through the development of drugs for tropical disease or a biological threat, such as COVID-19. Four have been awarded since the pandemic began for COVID-19: to Moderna, BioNTech, Pfizer and Gilead for their vaccines and antivirals. Neither of these programs are impacted by Congress’ recent actions, and so far, the FDA has granted one voucher under the tropical disease program this year: to Bavarian Nordic for its chikungunya virus vaccine Vimkunya. Bavarian Nordic has already indicated plans to sell the voucher “when appropriate.”

Opponents of the voucher programs say the fast passes are not doing their job to expedite the approval of drugs to help fill unmet needs in the rare and tropical disease communities. In a December 2024 paper, U.K. researchers Piero Olliaro and Els Torreele called the program “a misconceived quid pro quo, whereby much is given for little public health return, promoting and rewarding monopoly pricing of high-revenue products, with no strings attached—which indeed makes it attractive to pharmaceutical companies and investors.”

Bigger companies that earn or buy the vouchers use them to skip the line at the FDA for any drug they want. These vouchers are hard to track, as the companies do not have to report exactly where they got the voucher from when they use them. The FDA in recent years has occasionally posted Federal Register documents noting that a voucher was used for a particular drug, but these documents do not indicate where the voucher came from. From various records, it’s clear that many major blockbuster drugs of recent years have used these hall passes, from Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro, to AbbVie’s Rinvoq to Gilead’s portfolio of HIV meds and many more.

In mid-February, Alnylam Pharmaceuticals cashed one in for a speedy review of Amvuttra in ATTR amyloidosis with cardiomyopathy, an indication that is one of the hottest market battles at the moment with offerings from Pfizer and BridgeBio now available. Vertex Pharmaceuticals did the same in July 2024 for cystic fibrosis triple med Alyftrek, receiving an FDA nod less than six months later, in December 2024.

Novartis has by far been the most frequent patron of the fast passes, with as many as eight bought or earned over the years. The company has used the passes on Mayzent, Beovu, Kesimpta, Fabhalta and Kisqali, according to records. Gilead has spent as much as $621 million on known purchases of priority review vouchers.

Olliaro and Torreele argue that the program does not actually encourage drug sponsors to ensure the availability of the medicines that get approved under the program, especially for tropical diseases. For instance, the makers of tuberculosis therapies Sirturo and Dovprela, a medicine that was approved under the tropical disease program as pretomanid, have been criticized for keeping the prices for the therapies too high to help in countries with a high tropical disease burden. Sirturo is manufactured by Johnson & Johnson while Dovprela (previously pretomanid) was developed by the TB Alliance.

Frisk and Winton are aware of the criticisms but say that the rare disease program is working. You just have to look at the ramp up of drugs that have received a voucher over the years, with more handed out recently. That means that more companies are making these drugs and more rare diseases are getting new options for patients.

As for the criticism of a handout for Big Pharma, Winton says this is a tax neutral program. No taxpayer funds are being given to these companies; it’s simply a market-based solution that ultimately helps smaller companies do what they do best: develop rare disease drugs for smaller populations.

“Some of these drugs may not be developed or invented at all” without the voucher program, Winton said. “These [vouchers] are not necessarily going to the 17th, 18th statin—not that there’s anything wrong with that—but these are also going to feed the cycle of innovation and bringing drugs to patients in the U.S. who have no other options.”

Planning Funerals

One pediatric rare disease that has particularly benefitted is Duchenne muscular dystrophy, which has had seven drugs approved under the PRV program, including four from Sarepta Therapeutics. Each time, Sarepta sold its voucher and used the funds to continue its clinical programs.

Another rare disease that now has multiple options is spinal muscular atrophy. Winton previously worked at Biogen as head of the SMA franchise, where he oversaw work on Spinraza, which received a PRV in March 2017.

“That disease state has completely changed. You were used to planning funerals. And now you’re celebrating birthdays and you’re celebrating graduation into high school,” Winton said. “That’s an amazing success story.”

These patients now have several different modalities to choose from, including Novartis’ gene therapy Zolgensma and Genentech’s Evrysdi, both of which received priority review and were granted vouchers at approval. These seminal approvals of complex technologies like gene therapy have also helped fuel other innovations in the modality, which is another legacy of the PRV program, Winton noted. Similarly, Biogen advanced its antisense oligonucleotide technology with Spinraza, which earned a voucher in March 2017 and was sold for $103 million last year.

“When you talk to patients, when you talk to the rare disease community, the one thing they always say is ‘move faster.’ The one thing they don’t have is time,” Winton said. “The message we always take away when we talk to them is try to work hard or hurry up. This program does that. It speeds up our ability to get drugs to market. It speeds up our ability to do more research.”

About the data: BioSpace compiled the list of priority review vouchers through dozens of sources, including the FDA, Federal Register, SEC, GAO, company reports, news articles and more. Still, the list may not be comprehensive, as some PRV transactions go unreported.