Long considered resistant to economic downturns, the pharmaceutical industry may face a greater challenge this time around as GLP-1s dominate and the population grows older.

With GLP-1s making the pharma industry more exposed to consumer spending than ever, the tariff chaos could break pharma’s recession-resistant reputation.

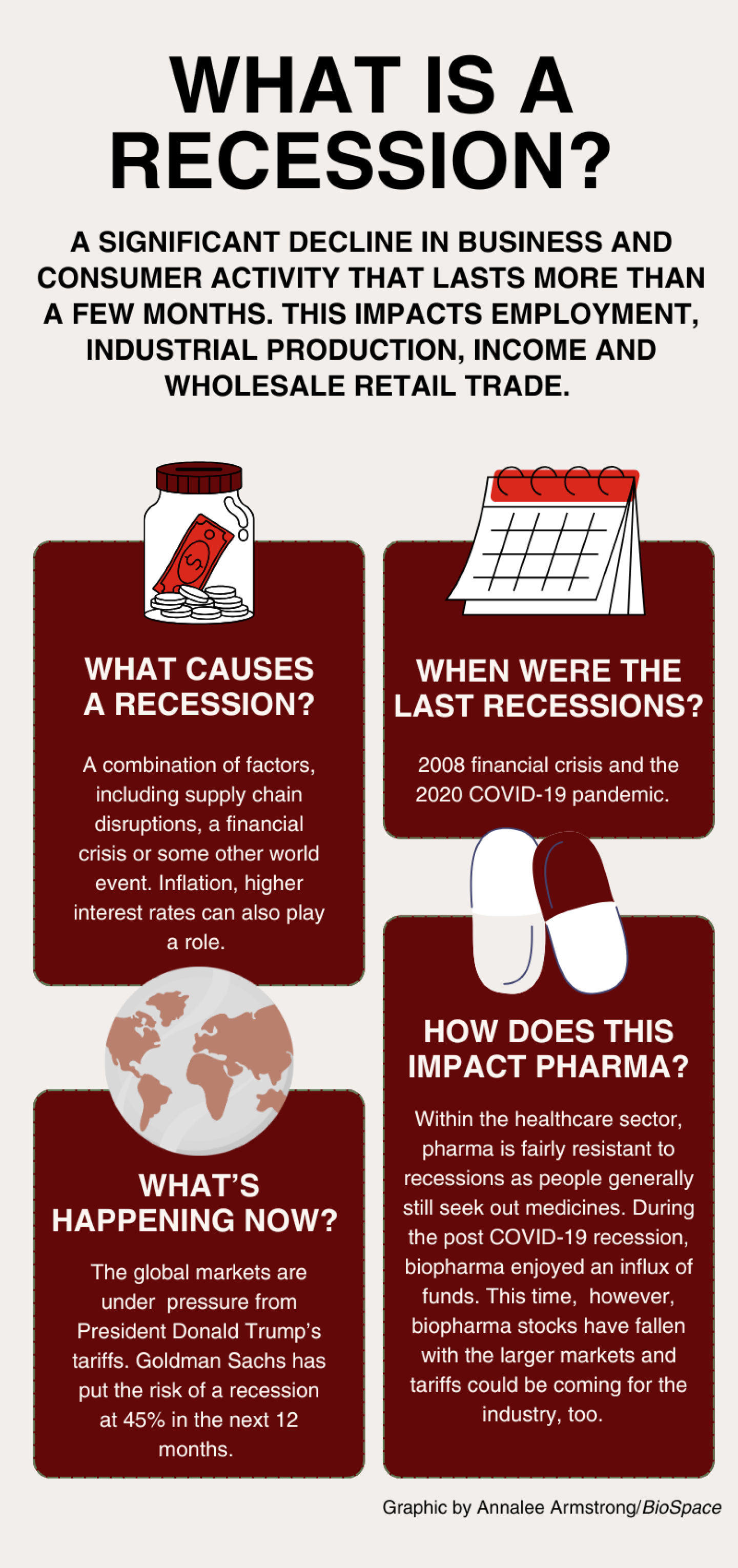

And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. If the world does indeed fall into a recession following the widespread tariffs put into place by President Donald Trump—as many indicators are suggesting it will—pharma could be particularly vulnerable. With the U.S. population growing older and suffering from more chronic diseases, personal healthcare expenses are on the rise for everyday people who could be forced to make difficult decisions like skipping medications.

The most significant recession in recent memory was the 2008 financial crisis, which was spurred by the collapse of the housing market and financial systems in the U.S. More recently, a shorter recession cropped up due to the pandemic. In both cases, pharma was largely immune. You have to buy your medicines even if the economy is tanking.

“The last two recessions the pharma industry has fared pretty well,” Arthur Wong, senior director of corporate ratings, healthcare, at S&P Global Ratings, told BioSpace. “People can’t really skip their prescriptions.”

According to Jefferies, pharma outperformed the S&P 500 through both recessions and in the years immediately following, because the industry is “overall a more defensive beneficiary of money flow in economic downturns.”

In the case of COVID, biopharma even enjoyed an influx of funds as investors poured money into the industry as it raced to develop vaccines and medicines that could stymie the rampant global outbreak. Jefferies said that pharma outperformed the S&P 500 by about 10-20% during that recession.

But this time around, things are different, experts say. Since those two events, GLP-1s have risen precipitously, but insurance coverage has not followed as neatly. That means the market has been defined by consumers, with many more patients pocketing the costs of GLP-1 medicines themselves. Trump also just nixed an executive order from his predecessor Joe Biden that expanded Medicare coverage for the therapies, cutting off another avenue for access—at least for now.

Wong told BioSpace he expects GLP-1s to take a hit if a recession does settle in. “You’ll still see growth,” he predicted, “it’s just that you will see a slowdown in adoption with things like this,” as patients back off paying out-of-pocket for weight loss medications.

Moreover, healthcare has grown as a larger portion of the GDP since the early 2000s, Wong noted. The population has aged, meaning more of them have chronic health conditions and are taking prescriptions for longer. Healthcare is becoming a larger part of people’s personal budgets. It remains to be seen how they will weather a recession.

“Depending on when the next recession hits, how deep it is, is it going to have a bigger impact?” Wong asked. “I would guess yes.”

Paying Up Front

Before the recession fears, insurance companies had faced increasing pressure to open up coverage of obesity medications. Wong said he thinks that now is not the right time to try to convince insurance companies to shoulder the cost because they are facing the same macro headwinds as any other industry and are beholden to their shareholders.

“The health insurers are all struggling and trying to control their medical-cost ratios,” he said.

The argument posed by companies like Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, the GLP-1 market leaders with tirzepatide and semaglutide, respectively, has been that their products can eliminate downstream health challenges. Both have pursued indications beyond just weight loss. Semaglutide, approved as Wegovy for weight loss, has been approved for reducing cardiovascular risk and for kidney disease, while Lilly nabbed an FDA nod for sleep apnea for Zepbound. Insurers just will not see this as the right time to make that down payment, Wong said.

“I think they can agree that they see savings down the road, but are they willing to pay for it up front? And is there money in the budget right now to pay upfront?” Wong asked. “They buy into [the idea of these drugs]. It’s just at what level of adoption [and] how aggressively can they provide coverage in this current environment.”

Even with covered drugs, the out-of-pocket expenses can be high. While it’s easy to assume that people will continue taking their medicine, Wong said that during the previous recessions, there were reports of “pill-splitting,” when people cut doses to make their prescriptions last longer or delay refilling.

“Before we go overboard, [pharma’s] still recession resistant,” Wong said. “I don’t think it was ever recession proof, but it is still recession resistant. I think it becomes less recession resistant as we go on, just because healthcare spending is a bigger part of the pie in terms of people’s budgets.”

The Tariff Threat

This moment for GLP-1s also comes as pharmas are directly battered by tariff uncertainty,, which Wong says the industry has “sidestepped”—for now.

Shares of Eli Lilly, now the largest pharma by market cap, have declined 12% in one month from a high of $864 apiece on March 24, wiping out $95.4 billion in market value. Novo, which takes the fourth slot below Johnson & Johnson and AbbVie in terms of market cap, has lost $72.4 billion in market value in the same time period, with shares falling 26% in one month to $63.64 at close Monday.

Jefferies said that the macro uncertainties due to the tariffs “have triggered a continued flight to safety,” on the markets.

“We expect macro to have the steering wheel,” the firm said.

Lilly CEO David Ricks told the BBC last week of the tariffs that “it’ll be hard to come back from here.” While much of the innovation in pharma is done in the U.S., Ricks said that the industry relies on global locations for production, including active pharmaceutical ingredients.

According to a recent survey from the industry group BIO, nearly 90% of all U.S. biopharma companies rely on imported API for FDA-approved products. If tariffs were imposed on Europe, half of companies would have to find new research and manufacturing partners, while 79% with Chinese contracts would be greatly impacted if that country is levied with huge tariffs.

“We have to eat the cost of the tariffs and make trade-offs within our own companies,” Ricks explained. Those trade-offs would include layoffs and reductions in R&D first and foremost, which Ricks called “a disappointing outcome.”

One expert who spoke to Truist Securities called the panic an overreaction and instead insisted that it’s a great time to be investing in biopharma. This person “sees this whole process of tariffs as a ‘revolution,’” to bring assets back to the U.S. to guard against unforeseen events like a war or another pandemic.